The Olympic legacy of Park City

Defining the next generation of winter athletes

Winter/Spring 22-23

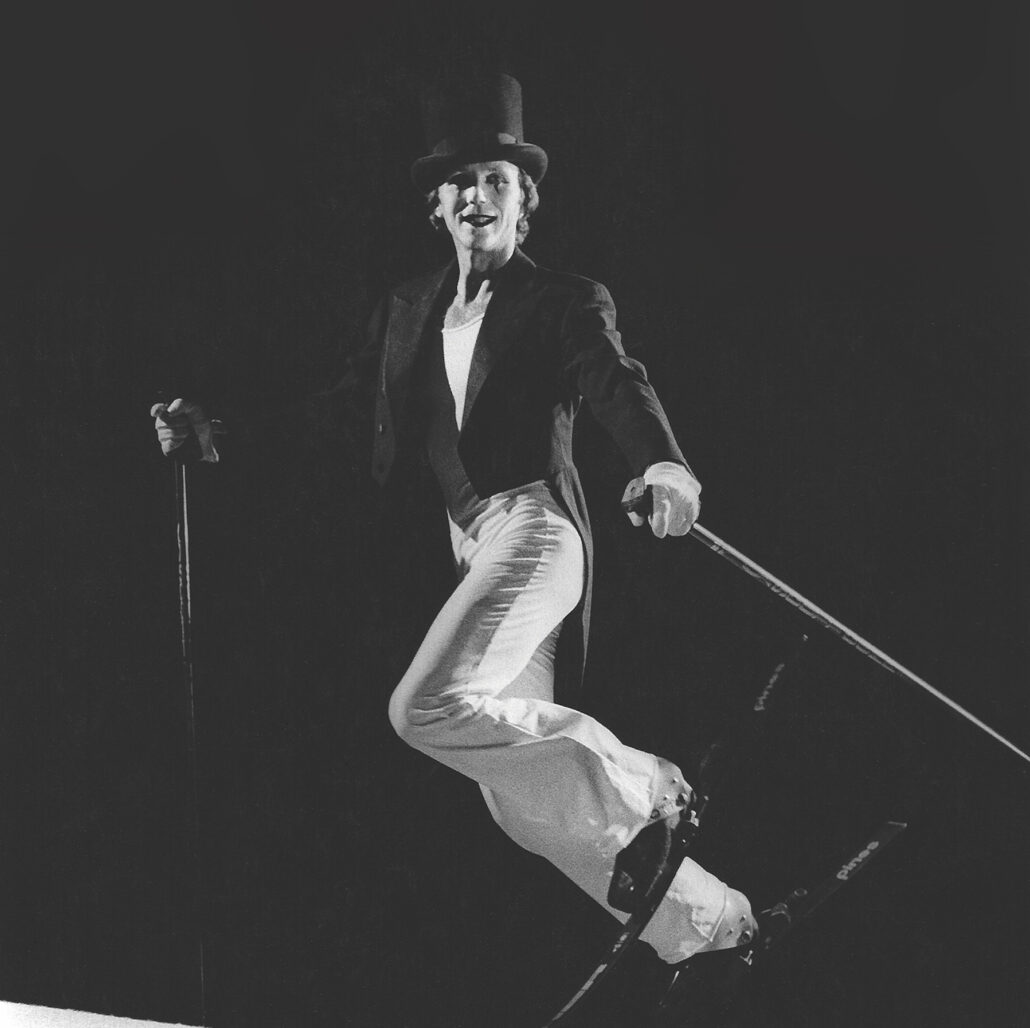

Written By: Ashley Brown | Images: Courtesy Utah Olympic Foundation

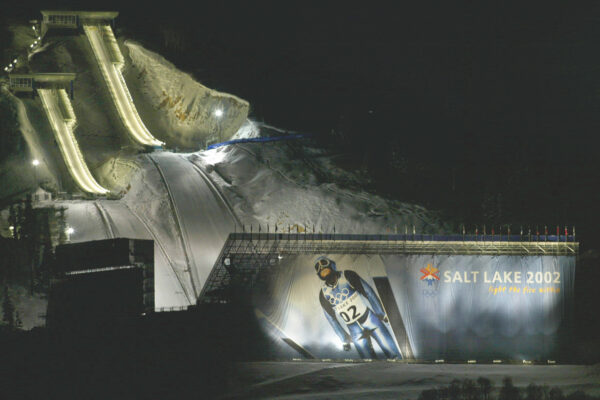

The 2002 Winter Olympics permanently altered Utah’s landscape and culture. In 1995, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) awarded Utah the event, and in the seven years leading up to the games, the state underwent major upgrades — including the construction of the TRAX light rail system and University of Utah dorms, which served as athlete accommodations. Most importantly, the state built or renovated 10 competition venues and five non-competition venues.

These venues have proved to be one of the most rewarding outcomes of the 2002 Olympics. The winter sports centers are scattered between Ogden and Provo, including four in Park City and the Wasatch Back: Utah Olympic Park, Soldier Hollow Nordic Center, Deer Valley Resort, and Park City Mountain. The lives of many locals have been enhanced because of access to these Olympic venues.

“Having every venue continue to be used as fully as possible is unusual in the Olympic movement,” explains Fraser Bullock, who served as COO and CFO for the Salt Lake Organizing Committee for the Olympic and Paralympic Winter Games of 2002 (SLOC) and is currently the president and CEO of the Salt Lake City-Utah Committee for the Games, which is involved in trying to bring the games back to Utah in 2030 or 2034.

Ongoing access to these well-kept facilities has molded the next generation of winter athletes. A Utah athlete has made it to the podium in every Winter Olympic Games since 2006 — thanks in large to their ability to train at world-class venues.

“The first thing the games have done is help many of our children be inspired by the games or inspired by the facilities that are there, so the participation is way up in our communities and our children,” Fraser explains.

In addition to inspiring and supporting local youth, the venues also attract athletes from around the world. “Because of the infrastructure in place, we have people who moved to Utah to train here — about 40 percent of the team [Team USA] that competed in Beijing lived and trained in Utah for some portion of their experience,” Fraser explains, and adds, “The other thing we have is athletes from over 30 countries who come and train here every year. … We are an international destination.”

For Parkites, this reality is palpable. A trip to the grocery store or gym reveals a rich combination of languages and a slew of different international team uniforms. Many Olympic-related organizations, like U.S. Ski & Snowboard, are headquartered in Park City.

In the two decades since the 2002 Winter Olympics, there has been a noticeable shift in the state culture; Olympians come to train and live in our state and local athletes have the tools they need to flourish.

“We have benefited tremendously from the games in 2002,” Fraser says, noting that he sees infinite positive outcomes from hosting the games again. “Having our children and grandchildren able to experience the games would be marvelous for the next generation — as well as the opportunity to unify our community again,” he explains.

The $76 million dollar endowment from the last Olympic Games enabled venues to operate at world-class levels. “The success [of the venues] has been greater than we ever dreamed,” Fraser exclaims. “Those funds are running out. We need to reendow at a higher level to hopefully permanently endow sport in Utah for our communities and our children.”

Fraser and the rest of the Salt Lake City-Utah Committee for the Games are involved in an ongoing bidding and communication process with the IOC. Their goal is to present Salt Lake City as a potential 2030 or 2034 Olympic destination. Already, the U.S. Olympic & Paralympic Committee (USOPC) cast their vote favoring Salt Lake City.

“We continually talk about Utah as being one of the best destinations in the world for the games because we have all the infrastructure in place. We have an experienced team that’s done it before. We have a welcoming community that’s thrilled to have the games again,” he says.

Fraser hopes to see the culmination of the committee’s hard work when the IOC announces the 2030 host city in May 2023. If Utah doesn’t win the bid for the 2030 games, he will continue working for 2034.

For Fraser, hosting the games again is an opportunity to celebrate diversity and diminish cultural, religious, and linguistic barriers. “At the end of the day, what the Olympics mean is bring- ing people from around the world together to celebrate human achievement through sports,” he states. “It’s ultimately the countries coming together that makes the Olympics so meaningful.”